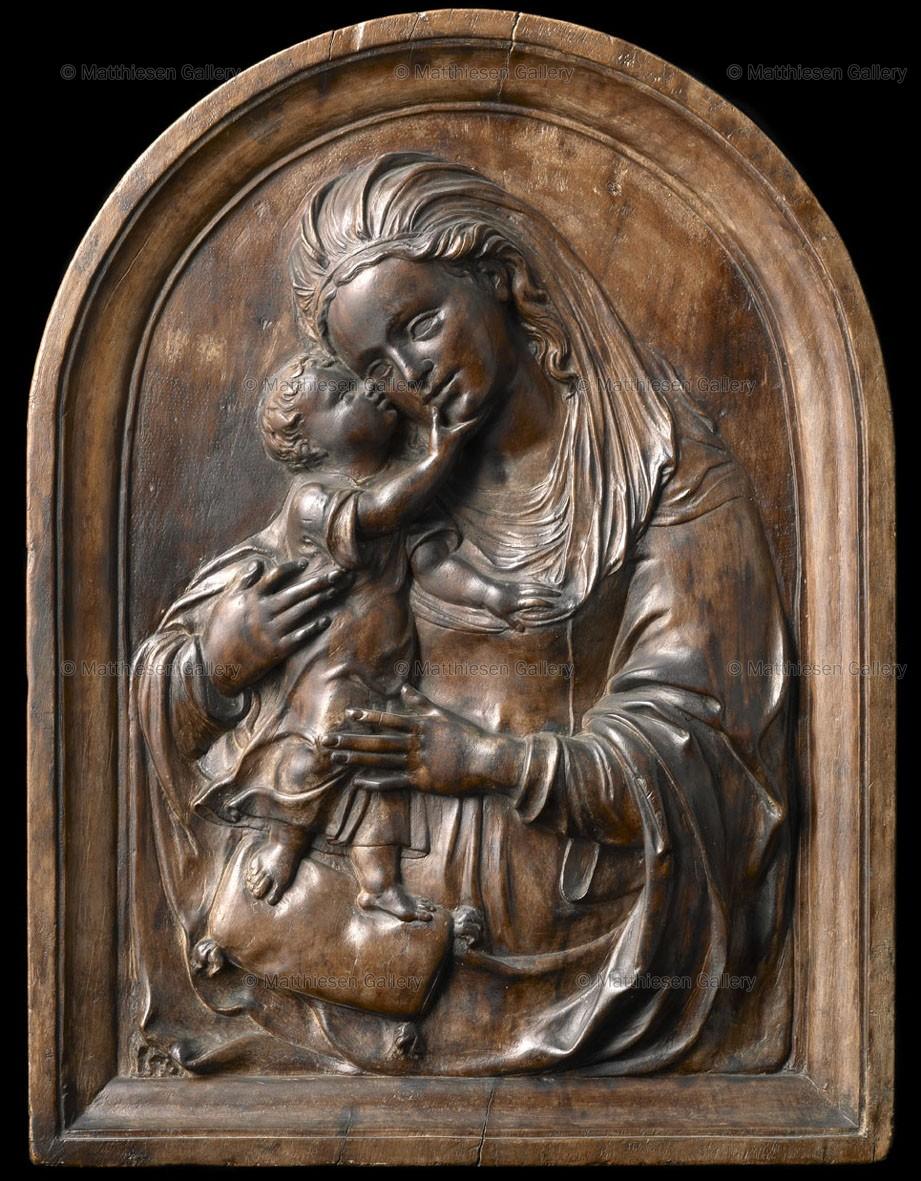

The Virgin and Child(Gregorio Pardo)

GREGORIO PARDO

(Burgos? fl. 1513 1551)

21. The Virgin and Child

c. 15481550

Walnut relief

58 x 36 cm (19 ⅝ x 14 ¼ in.)

PROVENANCE: Benedito Collection, Madrid; Alcala Subastas, December 2008, lot 565

Pardo organized his composition in three concentric circles; the first is formed by the strong

curve of the Virgins head, inclined towards that of the Child and is emphasized by the Childs

outstretched arm which, in a spontaneous childlike gesture, reaches towards his mothers face.

This gesture is the narrative focus of the work, and is also where Pardo concentrated the

greatest volume in his relief. The Virgins enveloping of the Child in her arms forms the second circle,

and, in forming the third circle, Pardo dealt with the challenge of maintaining his tondo-like

composition by placing under the Childs feet a cushion, which curves to meet the undulating folds of

the Virgins mantle. By using such a rich interplay of sensual forms and gestures, Pardo gives the relief

not only formal coherence and narrative unity, but also manages to portray a deeply sympathetic

expression of maternal love.

Two other reliefs attributed to Pardo, both depicting the Virgin and Child and both in Toledo, share

several features with the present work. In one of these, an alabaster relief in the parish church of San

Nicolás, the Child also reaches towards the Virgins face with the same open-handed gesture. Equally,

the treatment of the Virgins veil is noticeably similar to the one in the Church of Santa Leocadia, and

in fact even displays a similar pattern in the folds (Fig. 1).1

This particular gesture, where the Childs hand is placed on the Virgins chin, had been an established

form of sculptural iconography in the Cathedral of Toledo and dates back at least to La Virgen Blanca,

a fourteenth-century work renowned since its creation as one of the most beautiful sculptures in the

round in all Europe (Figs. 2a, b). No doubt Pardo had been deeply influenced by this work, and had

taken note of this specific gesture, possibly even making sketches to refer to later, as this particular

detail is almost identical to the Childs gesture in the present work.

Another similar alabaster tondo depicting the Virgin and Child is in the Cathedral of Burgos (Fig. 3),2

where it is attributed to Felipe Bigarny (Felipe Vigarny, Felipe Biguerny or Felipe de Borgoña) who is

believed to have been Gregorio Pardos father. Here, the somewhat inflated folds of the Virgins veil,

which are lent definition by the cord tying them together, the standing pose of the Child and the softness

of the Virgins hands are all traits shared by the present work as well as the two other alabaster pieces

in Toledo.

These similarities, not to say repetitions, almost make the attribution of Pardos Virgin appear

interchangeable with that of Bigarny, and in some cases this is more than just an impression. The

important sculpture workshops such as those of Pardo and Bigarny were at times tasked with

honouring a variety of commissions for identical objects. Therefore, the sculptors actually made models

of some of their most popular and in-demand compositions, either in wood or in moulded clay,

specifically to be used in their workshops as a guide for their apprentices in executing these

commissions so that no detail or aspect of their initial composition should be lost or diluted in the

manual transference that is inevitable in any large workshop.

The present relief is an important addition to the corpus of Pardos known work. Firstly, because it is

the only known example in walnut; and secondly, because it illustrates the strong stylistic ties Pardo

had to the work of his father. The work exhibits many details that derive directly from Bigarnys

workshop but, equally, illustrates a palpable shift away from the superficiality of surface detail that

typified the earlier sculptors work, specifically a shift towards an active pursuit of beauty, elegance and

harmony of forms, and away from any shrill sense of expressionism.

Pardo strove for and also achieved a sense of physical beauty in the Virgins face in order to deliberately

underscore the sense of intimacy between mother and child, which is so distinct in this relief. The

Virgins elegant, tapered hands are a recurring feature in Pardos work and, in line with his workshop

technique, conform to the formula of joining the centre fingers and separating the index and the little

finger. Also standard is the Virgins hairstyle arranged in bulging locks, with one lock left hanging in

front of the ear: a style founded in the Burgos workshop of Diego de Siloé.

This relief also illustrates the significant shift towards stylistic simplicity and an abandonment of the

medieval sense of ornamentation, with its attendant luxury and use of jewels and costly garments.

Above all, it is the anatomical precision and clarity of the figure that are the hallmarks of Pardos

innovative style. The present Madonna is dressed in the Roman fashion in a simple tunic and mantle,

which is decorated simply with a narrow frieze-like border. The tilt of the Virgins head and the childs

up-reaching arm mirror the composition of Donatellos Pazzi Madonna (Berlin, Staatlichen Museen).

A comparison of the present work with other known works by Pardo reveals several formal similarities

with one of Pardos most renowned works, and, indeed, one of the greatest masterpieces of the Spanish

Renaissance. This is his relief made for the stalls in the choir of the Cathedral of Toledo that depicts

Saint Idlefonso Receiving the Cassock of His Order from the Virgin (Fig. 4). The alabaster relief was

commissioned from the artist in 1548 by Diego López de Ayala, an outstanding humanist and art

connoisseur.3 López de Ayala had also commissioned from Bigarny carvings for the back of the

archbishops throne. When these works were left unfinished upon Bigarnys sudden death in 1542,

Lopéz de Ayala conferred the commission onto Pardo, and, in fact, all of the subsequent sculpture

commissions for the Cathedral.

If we compare the present Virgin and Child with the Virgin in the choir relief, we see almost identical

veils, right down to the arrangement of certain folds around the hair. So similar in fact are these two

reliefs in style and form that it is difficult to determine which one was carved first.

Gregorio Pardo was the first son born to Bigarny, and from an early age took the name of his mother,

who came from a noble Burgos family. However, later, as a sculptor in Toledo, Pardo signed himself

Gregorio Bigarne, so it is likely he kept his fathers workshop in Toledo. He started to be put on

contract before 1537, that is, before his fathers death, and received so many prestigious commissions

often far removed from each other that he eventually declined any obligation to complete commissions

undertaken in Peñaranda de Duero and Burgos. Instead, he limited himself to only those contracts that

would best benefit his widowed mother and brothers and secure the family business.

After 1537, Pardos fortunes are linked to his father-in-law, Alonso Covarrubias, who was senior master

of the Cathedral and responsible for the most important sculptures, such as the decorations for the

Portada de la capilla de la Torre (1537). Also connected with Covarrubias are Pardos royal

commissions in Madrid for Don Alonso de Castilla, Bishop of Calahorra (1538, Museo Arqueológico

Nacional).4 Between 1539 and 1542, Pardo carved reliefs depicting The Coronation of the Virgin and

The Miracle of Saint Leocadia, and a few years later carved the exceptional walnut cajoneria, or

wardrobe, in the anteroom to the chapterhouse (1549), which is a masterpiece executed in the artists

now unmistakable style.

This brilliant artistic career was suddenly cut short around 1551, and Pardos last commission was for

the sepulchre of Don Fernando de Córdoba, head of the Calatrava Order, which was to be placed in

the chapel he founded in Almagro (1551, Ciudad Real). Unfinished at Pardos death, in 1552, the tomb

was completed by Covarrubias with the help of Vergara the Elder, and, most importantly, Bautista

Vázquez. It is particularly significant that it was Vázquez who supervised the completion of Pardos

final project, as his work also came to be typified by contained emotionalism, formal balance and

idealized aesthetics.5

The Cathedral of Toledo contains the highest concentration of important works from the Spanish

Renaissance. When Pardo first arrived to begin work on the choir decoration and the other works

commissioned by Tavera, he was the only sculptor working in a style opposed to that of Alonso

Berruguete, and it is partly this maverick status vis-à-vis the great Castillian master that establishes

Pardos place in the history of Spanish art.

The present work is a rare and important addition to the small number of extant works known by

Pardo, the scarcity of which is partly the result of his premature death and partly due to the loss of

many of his works. Based on its simple style and sense of Renaissance purity, the present relief can be

dated to between 1548 and 1550, at the peak of Italian Mannerism, when Pardo, nevertheless, was still

basing his aesthetics on the lucidity and clarity of classical models.

1 J. NICOLAU, in Archivo Español de Arte, 1983, pp. 416418.

2 I. DEL RÍO DE LA HOZ, El escultor Felipe Bigarny (h.

14701542), Junta de Castilla y León, Valladolid 2001, p.

238, fig. 53.

3 I. DEL RÍO DE LA HOZ, El Coro de la Catedral de Toledo,

Col. Cuadernos de Arte Español, no. 52, ed. Historia 16.

4 M. ESTELLA, Los artistas de las obras realizadas en Santo

Domingo el Real de Madrid, in Anales del Instituto de

Estudios Madrileños, XVIII, 1980, pp. 4165. See also A.

BUSTAMANTE GARCÍA, Forment, Bigarny y Gregorio Pardo,

in Boletín del Museo e Instituto Camón Aznar, XXXIV,

1988, pp.167171.

5 The epitaph for the tomb was written by Canon Juan de

Vergara, and published in a work of Alvar Gómez published

in Lyon by Gaspar Frechsel, Alvari Eulaliennno Eidyllia

aliquot sive poemática (Lyon, 1558). Here, one can read of

the special and pronounced affection that Covarrubias felt

for his son-in-law, and how he wrote an elegy to Pardo and

his wife (cited in J. MARTÍ Y MONSÓ, Estudios históricoartísticos

relativos principalmente a Valladolid, Valladolid

1901 (facsimile ed.), p. 52.

Benedito Collection, Madrid;