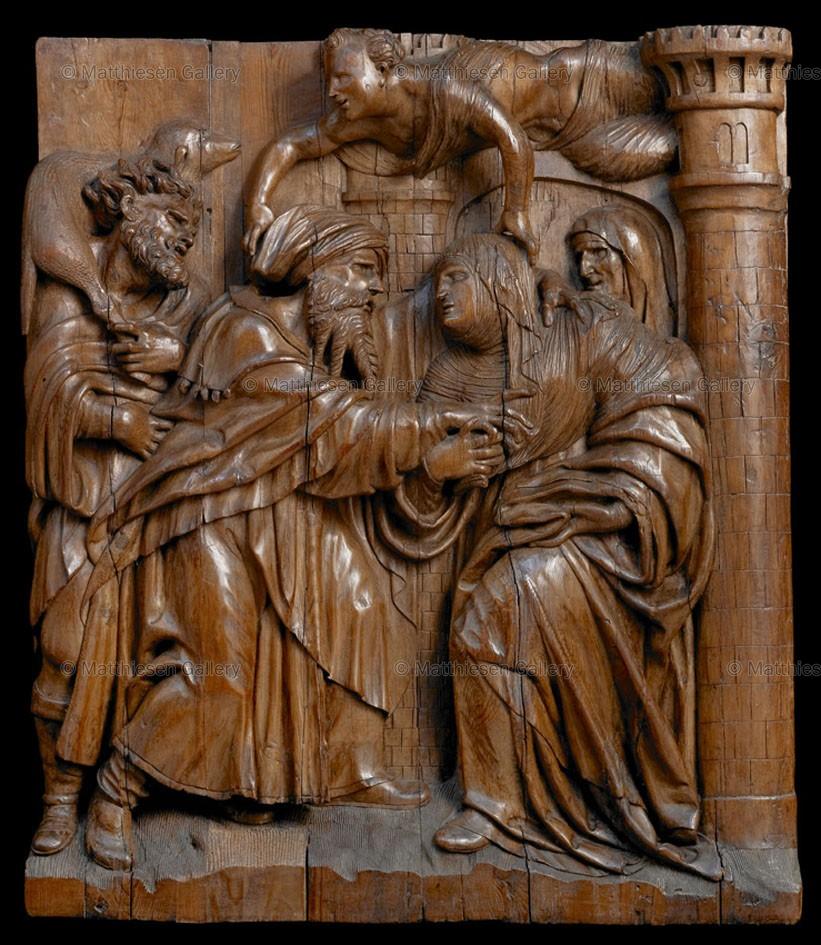

The Meeting at the Golden Gate(Francisco Giralte)

FRANCISCO GIRALTE

(Valladolid c. 1500 1576 Madrid)

20. The Meeting at the Golden Gate

Pine, carved in high relief

135 x 114 cm x 21 cm (53 ⅛ x 44 ⅞ x 8 ¾ in.)

PROVENANCE: H Lüttgens, Aachen; Mrs Clifford Ambrose Truesdell, New York

Spain at the end of the fifteenth century and well into the middle of the sixteenth was overflowing

with churches and altarpieces, as well as tombs, choir stalls and facades, all of which were

decorated with sculptures and reliefs. For sculptors this level of development was unprecedented,

both in the quantity of works produced and in their overall quality. This large pitch-pine relief

depicts the moment the aged Anna met her future husband. Joachim. Despite their advanced age, the

pair would be blessed with a son, Joseph, who would later serve as father to the infant Jesus.

Stylistically, the relief is typical of Francisco Giralte and must have been carved originally as part of one

of the many large altarpieces made during this period or, since it is without polychrome, it may have

formed the decorative backing above a series of sumptuous choir stalls.

We do not know if Giraltes father who must surely have been French with such a surname first

came to Palencia in search of greater fortune before his son arrived in the city.1 The younger Giralte is

known to have had firm ties to Palencia at an early date, where he probably owned land. Certainly

Francisco established his first professional contacts in the city where he received an early commission.

In any case, it is known that Francisco was married in Palencia in 1547 and that he had a sister, who

married the sculptor Manuel Álvarez, a pupil of Alonso Berruguete, as indeed, was Francisco Giralte

himself. After having trained in his masters workshop between 1532 and 1535, Giralte went on to

develop his own style, which, while distinct in many ways from that of Berruguete, is nevertheless seen

as faithful to the work of the Castilian master.2

As the director of his own workshop, Francisco Giralte received commissions for numerous altarpieces

throughout his entire life, assuming a risky management strategy, technically as much as artistically,

and, in some respects, economically as well, because the demand for such works far outstripped the

capacity of Giraltes workshop.

The aesthetics of The Meeting at the Golden Gate exhibited here illustrate the incorporation of

successive influences that are both recognizable in and indicative of the work of Giralte. We can analyse

this adoption of models: the shortened proportions of the figures and the five heads are all characteristic

of Giralte, and both features are emphasized by the square support, which indicates that the relief may

originally have been part of the lower mid-level of a large retablo, or the backing of choir stalls, as said

above.

This particular subject always depicted as the aged saints embracing

before a monumental city gate is included as part of the Life of the

Virgin Mary. The individual scenes of reconstituted altarpieces tend

to follow a pre-established iconographic order, which is medieval in

tradition. This iconographic formula is also found in the graphic

depictions of religious narratives and particularly in those of

Flemish printmakers, who were fond of including anecdotal

elements, in much the same way as in this relief by Giralte, where

an angel, approaching over the heads of the saints, serves to

communicate the heavenly benediction of their betrothal.

Interestingly, on this occasion Giralte borrowed his composition

from a work by Pedro de Berruguete, Alonsos father, as can be seen

in a painting dated to the last quarter of the fifteenth century in the

Church of Paredes de Nava, Palencia (Fig. 1). Even greater proof of

this connection is illustrated in the Palencian subjects of his master

Alonso.

The narrative focus of the composition is the shepherd, who carries

a lamb slung across his shoulders. His position in the relief, on the

far left, is made all the more noticeable by its slightly unstable and

truncated impression. No doubt this sort of detail would have been

pleasing to Castillian eyes of the time. The head of the shepherd is

magnificent and corresponds to the model that Giralte and his companions explored in the walnut choir

stalls of the Cathedral of Toledo, where he had been the foreman of Alonsos Berruguetes team.3

From 1550 onwards, most depictions of The Meeting at the Golden Gate did not feature either an angel

or a shepherd: these figures were not part of the standard iconography. However, the figure of the maid,

whose presence as witness is consistently referred to in the Apocrypha, was generally retained. Perhaps

in a bid for even greater expressiveness, Giralte depicted this particular figure as rather old, in fact, as

old as Saint Anne herself, perhaps to symbolize the sage gravity of her role as witness of the holy scene.

All in all, these altarpieces were constructed as enormous stagings of the divine mysteries. The

sculptures were specifically designed and executed to capture and, just as importantly, to hold the

attention of the faithful, who would pray before them everyday, throughout their entire lives. To

maintain an element of surprise in their depictions of such familiar narratives, artists looked for new

approaches to composition, pose and expressions to enliven these sacred scenes.

At first glance the bodies of the characters seem curious because they are not treated as a whole, but as

parts: that is, heads, hands and drapery. For the most part, the facial types derive from Berruguete, a

particular feature being the open mouth with a very high upper lip, as in the Angel of the Anunciación (Figs. 2a, b) from Berruguetes altarpiece of La Mejorada (Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid).

His faces are typified by an emotional expressiveness particularly evident in Saint Anne and her maid

that communicates a deep agitation of the spirit, and constitutes possibly the defining characteristic of

Alonso Berruguetes work: his urge to release the intangible and the divine from the solid as in the relief

of La Visitación from the Convent of Santa Ursula in Toledo (Fig. 3).

For example, in the present relief the head of the shepherd appears to follow a classical (almost Hellenistic)

model, and the locks of his long hair seem charged with energy, as well this humble figure might be in

witnessing such a divine moment. The first time we encounter a similar figure is in Berruguetes Adoration

of the Magi, from the Santiago parish in Valladolid (Fig. 4). In this composition, Berruguete appears to

have deliberately depicted the hands so that they appear odd, with strange fingers and in physically

impossible poses. The hands recall the template technique used for the choir stalls from Toledo Cathedral,

in which a variety of hands, feet and heads would be modelled from plaster impressions, and then later

incorporated by Berruguetes assistants into the figure for the corresponding seat.

The draperies in Giraltes relief are depicted in such thick, heavy folds they must surely have been

modelled on the cloths that made Castile famous in European markets and fairs. Like felt, the cloth,

when crumpled, formed great folds, and therefore, in terms of sculptural representation, was very

efficient for imparting monumentality and gravitas in the figures, regardless of their size. Giraltes style

has a tense monumentality, evident in the present relief. Doubtless, this aspect of his style was Giraltes

response to the influence exercised by Juan de Juni, whom he greatly admired, despite being, at the

same time, his rival in Valladolid. Both artists maintained a historical lawsuit in relation to the award

of the altarpiece commission for Santa María Antigua, Valladolid. The document relating to this

lawsuit is of major importance for our knowledge of Giralte because it provides us with most of the

facts that form his biography.4

Another particular characteristic of Giraltes work is his focus on detail, such as hairstyles and shoes,

and it is worth pointing out that this fondness for capturing specific minutiae grew out of his repeatedly

making sketches and drawings for silversmiths. To this decorative precocity belongs the beard of Saint

Joachim, a feature of the relief that could have come out of Felipe Bigarnys workshop, and that is

stylistically similar to one of that artists first sculptures for Palencia Cathedral.

Francisco Giralte is defined as an eclectic, an artist so driven to assimilate that he poached elements of

his style from his rival, Juan de Juni, such as the use of tight compositions that depend on a strong sense

of symmetry to maintain narrative focus and clarity in the subject depicted. This manner of arranging

the figures is clearly illustrated in the present relief.

Giraltes career can be divided into two periods, the first includes his first works executed in the

workshops of Palencia, sculptures of far-reaching effect, which were modelled closely on Berruguete

and which reflect the sense of drama and the movement typical of that master. During this period,

which comes to a close around 1548, Giralte made the altarpiece of the Cisneros in Palencia, one for

the Monastery of Valbuena (lost), and another for the Corral Chapel of the parish church La

Magdalena in Valladolid.

Giraltes second period is distinguished by his most important Madrid commissions, such as the famous

Chapel of the Bishop, a family chapel in the Plaza de La Paja, a spectacular funerary space that

anticipates the royal sepulchres of El Escorial (Fig. 5). Giralte secured

this commission as a result of the fame he had acquired from his work

on the choir stalls in Toledo Cathedral, which gained him entrance into

the exclusive circle of artists in Toledo who would oversee projects for

the budding Madrilenian court.

Around 1550, Giralte set up his new workshop and home in the heart

of Madrid, close to the parish church of San Andrés and the Chapel of

the bishop, when the city was being promoted as the new capital of the

kingdom. From the beginning of his independent career, he had made a

distinctive speciality of altarpieces just like Berruguete and his fame

in this genre led to commissions to design altarpieces for other artists.

Giralte was also hired to design several altarpieces in Madrid (most of

which are now lost), including one for the Church of the Almudena, two

for the Church of Pozuelo de Alarcon, as well as others, such as those

in Barajas and Ocaña (Toledo). The altarpiece from El Espinar survives

and Giraltes intervention in several others may also be recognized, for

example in the altarpiece in Colmenar de Oreja (Madrid).

The present relief must belong to Giraltes Madrilenian period,

specifically the 1550s, as it illustrates the artists predominating style. It

is probably a section of an altarpiece, and includes some necessary general workshop participation, as required of works of such dimensions, complex organization and

economic risk. The successful completion of these large-scale retablos demanded significant capital and

a teamwork of sculptors and artisans of the highest calibre.

The syncretism and evolution of Giraltes style is evident in his approach to characterization in The

Meeting at the Golden Gate. In an effort to renovate his art, Giralte had always remained alert to the

enduring appeal of earlier masters, such as Berruguete, as well as contemporaries and rivals, such as

Juan de Juni and Diego de Siloé. Truth be told, under the circumstances, Giralte was spoiled for choice,

working as he did side by side with the best sculptors of the kingdom. Giralte knew all of them and was

influenced by several. If, therefore, Giralte is now relegated to the second tier of Spanish Renaissance

sculptors, he should nevertheless be firmly placed just below the greatest of his contemporaries in

sixteenth-century Castile.

1 For a discussion of the sources of the name Giralte and a

good analysis of the work of both father and son, see J. M

AZCÁRATE RISTORI, Escultura en el siglo XVI, Colección Ars

Hispaniae, Plus Ultra, Madrid 1958, vol. XIII, pp. 187191.

2 For further discussion of Giraltes style see J. M. PARRADO

DEL OLMO, Los escultores seguidores de Berruguete en

Palencia, Universidad de Valladolid, 1981, p.163. The

influence of Michelangelo was felt in Spain after 1550; see J.

M. AZCÁRATE RISTORI, La influencia miguelangelesca en la

escultura española, in Goya, no. 75, Madrid 1966, p. 108.

3 Giralte worked on this project with Inocencio Berro and

Pedro Frias amongst other sculptors who were under the

direction of Alonso Berruguete.

4 A. MARTÍN ORTEGA, Más sobre Francisco Giralte,

escultor, in Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y

Arqueología: BSAA, Universidad de Valladolid, 1961, vol.

XXVII, pp. 123130.

H Lüttgens, Aachen; Mrs Clifford Ambrose Truesdell, New York