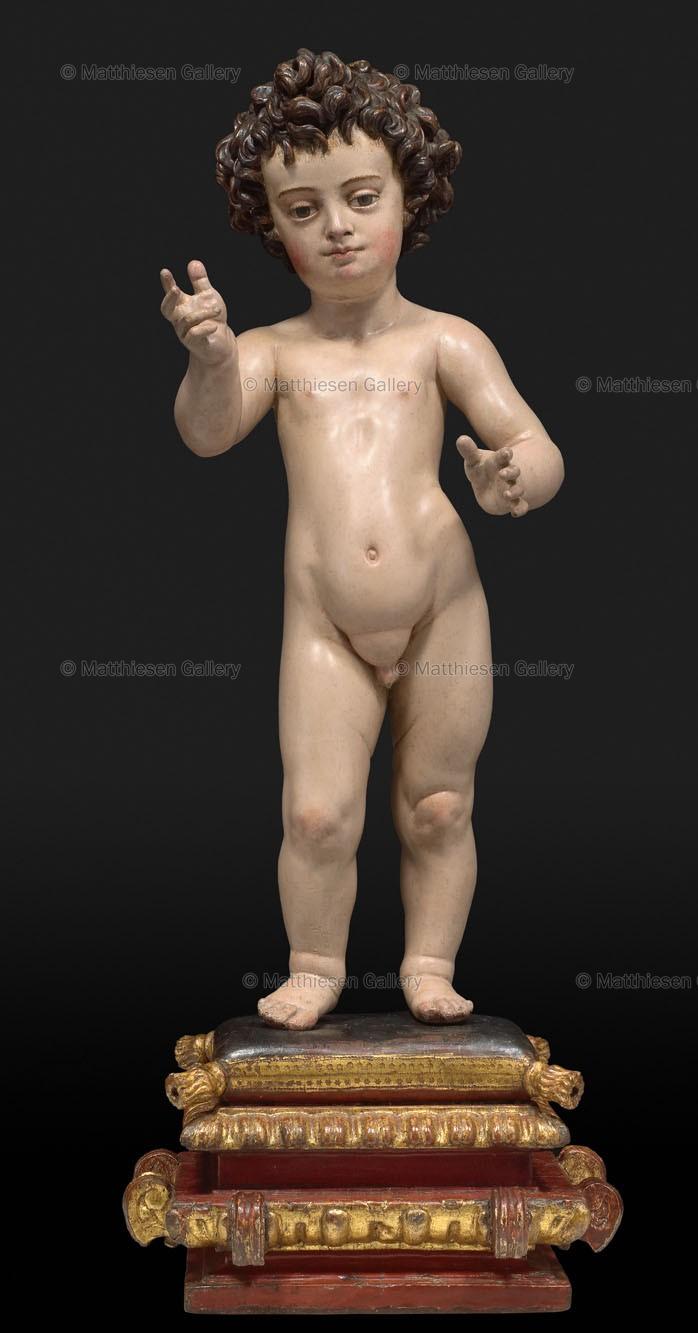

The Infant Christ(Juan Martinez Montanez)

JUAN MARTÍNEZ MONTAÑÉS

(Alcalá La Real 1568 1649 Seville)

11. The Infant Christ

Wood, polychromed, with rock crystal (eyes); the base of polychromed and gilded wood

85.1 cm (33 ½ in.)

PROVENANCE: Private Collection, New York

The religious fervour that arose in Spain out of the Council of Trent gave rise to several new

cults devoted to the veneration of the Eucharist, and the veneration of Christ incarnate. One,

the cult of the Dulce Nombre de Jesús, employed imagery that exclusively depicted Christ as

an infant, often nude, and standing, with the right hand raised in blessing, the left arm often

supporting the cross or another symbol of the Passion.

The earliest documented Infant Christ in Andalusian sculpture is a late work by Jerónimo Hernández

(c. 15401586) made around 1582 for the Confraternity of Quinta Angustia in Seville and now in the

parish church of Santa María Magdalena (Fig. 1). In the past, scholars associated this subject of the

Infant Christ specifically with Hernández, an artist who trained with Juan Bautista Vázquez the Elder

and worked in Seville during the last third of the sixteenth century. However, this subject is now

understood to be almost iconographic of the work of the Sevillian sculptor Juan Martínez Montañés,

based on his masterpiece of the subject dated to around 1606, which is conserved in the Sacristy of

Seville Cathedral (Figs. 2a, b).1 In the years that separate this work from Hernández sculpture, the

subject of the Infant Christ apparently evolved from the formers Mannerist boychild figure to the

more naturalistic infant type formulated by Montañés. It is the latter artists treatment of the subject

that subsequent sculptors throughout the first third of the seventeenth century took as their model for

the Infant Christ.2

Juan Martínez Montañés was born in Alcalá La Real, a village in the province of Jaén, which was also

the hometown of the Rojas (or Raxis) family of painters. Indeed, Montañés was initially taught by Pablo

de Rojas, and possibly worked for him in Granada. Montañés moved to Seville in 1587 in order to obtain

his masters licence for the opening of an artists workshop, and having married there, he remained in the

city for the rest of his life. He had arrived shortly after the death of Hernández, who had also been enticed

from his hometown (Ávila) to Sevilles vitality and artistic activity, and enjoyed a long and successful

career there. Famed as a technically brilliant sculptor in wood, and a profoundly religious man (though

reputed to be irascible and arrogant), Montañés also enjoyed a long and productive career in Seville and

made sculptures for the cathedral and various convents and monasteries. He also contributed to the

decorative renovation and adaptations of various church interiors to meet the demands of Tridentine

doctrine. Finally, and rather importantly, he made works for export to the Spanish colonies in the

Americas. This particular boom industry in Spanish Baroque art was centred in Seville, and contributed

significantly to that citys development as a thriving cultural and commercial centre.

The Churchs desire to promote this cult of the Eucharist in the

Americas and the associated increased demand for portable

tabernacles and sculptures proved of particular benefit to

Montañés, and he received several commissions to provide such

objects for Dominican and Franciscan convents throughout

Hispano-America. Concommitently in Spain, confraternities

devoted to the Eucharist were forming in the parishes and dioceses,

and with municipal support began to establish an annual tradition

of devotional processions, or pasos, of the Corpus Christi, which

were mounted with great pomp and celebration. Here, rather than

depicting Christ as a man, the main character in the procession

becomes Christ as the Holy Infant, who is presented conferring his

blessing upon the crowd with his right hand, while carrying the

cross in his left. Although these sculptures of the Infant Christ were

conceived to participate in the procession dressed in an

embroidered túnica, they were nevertheless carved completely with

great realism, and reflect a close observation of infant anatomy,

such as the fold of the buttocks at the top of the legs.

Although Professor Álvaro Recio believes that the 1606 work in

Seville is the artists only known sculpture of this subject, an Infant

Christ dated 1596 in the Church of Santa María de las Virtudes in

Villamartín, outside Cadiz (Figs. 2a, b) should be considered the

earliest example by the artist.3 The present work is a fully

autograph replica of the sculpture in Villamartín, with the addition

of rock crystal eyes, and like other cult statues of the Infant Christ,

would have been dressed. The Villamartín Infant Christ is

somewhat similar to Hernández earlier version, specifically in the long curls and chopped fringe of the

hairstyle, and the pose with the weight solidly placed on the left leg and the right leg slightly advanced,

a stance that is quite different from the sense of weightlessness and grace seen in the 1606 work,

although the present work does appear to feature a similar hairstyle of short, thick curls.

A comparison with the figure in Saint Christopher Bearing the Christ Child (1597) in the Colegiata de

El Salvador (Fig. 3),4 shows that at this earlier date Montañés approach to infant physiognomy is quite

different from his recognized autograph type from 1606. Here, the Child is depicted wearing a shirt

carved in only a few simple angular folds, and extending his right hand in blessing. The index and

middle fingers are slightly splayed, but the ring finger and little fingers are joined, a gesture that is

shared by the work in Villamartín, Hernández work and the present work, but not in the 1606 Infant

Christ, which has more naturalistically modelled hands with outstretched fingers.

Moreover, in both the present work and the Villamartín Infant Christ we see the same broad brow, full

chin, slightly arched eyebrows, a short, thin nose, and small closed lips. Also in both works, the wide, almond-shaped eyes, with a very slight bulge at the bottom lid, suggest a distant gaze, deliberately

removed from the viewer, again an impression that is very different from the naturalism and sense of

communion seen in the later work in Seville. However, the hairstyle of the Villamartín piece differs from

that in the present work. It is closely modelled, without volume, and ends in tendrils about halfway to

the shoulders, which separate to reveal delicate ears. This particular feature is repeated in another lifesize

Infant Christ on Tenerife in the Church of San Pedro, El Sauzal (Fig. 4). Here, the Child is fully

clothed in long robes that reveal only the feet and the Sacred Heart at the neckline, which is probably

a later addition.5 The fact that the Villamartín piece and the sculpture in Tenerife share similarly shaped

heads and fringed hairstyles therefore indicates that the 1606 Infant Christ could not have been the

sculptors earliest version of this subject, but instead must have evolved from these earlier works made

during the last years of the sixteenth century.6 These works were possibly influenced by the knowledge

of Dutch examples of the Christ Child that were incorporated into figure groups made for convents in

the Netherlands,7 and indeed certain stylistic features, like the almost triangular hairstyle arranged in

three small tufts to evoke his place in the Holy Trinity, which is shared by both the present work and

the 1606 sculpture, possibly derive from Flemish Mannerist engravings of the subject.

The present sculpture therefore illustrates an important step in the artists development of this subject,

the culmination of which is his 1606 masterpiece in Seville. Here, the addition of inset rock crystal eyes

and the somewhat rigidly posed legs, which are modelled in limited detail, result in a work which, while

not strictly naturalistic (at least, not in the sense of the 1606 sculpture), is nevertheless of great beauty

and refinement. Moreover, as is fantastically rare in Montañés, this sculpture retains its original

polychromy, which aids us in dating the work to between 1600 and 1606, a period to which Álvaro

Recio dates another sculpture of the same subject in the collection of Marañón Morales.

The base of the sculpture takes the traditional form of a cushion, though it lacks tassels at the corners,

above a moulded plinth, carved and decorated in an early seventeenth-century late Mannerist style with

an egg-and-dart border separated by flying volutes.

Montañés model for the Infant Christ proved so popular that his followers produced numerous Niños

in polychromed lead. One of these copies is in the Museo de Bellas Artes, Cordoba, and is attributed

to Juan de Mesa.8 This work shows a heightened sense of realism in the eyes and a softer and more

rounded approach to anatomy, and this distinctive infant type is also evident in the cherubim beneath

the Virgins feet in an Assumption by Mesa in the Church of Santa María Magdalena Seville, which is

documented to 1619

1 A. RECIO, Juan Martínez Montañés, Niño Jesús, in Teatro

de Grandezas, exhibition catalogue, Seville 2007, p. 232.

2 That is, until around 1637, when the arrival of the

Flemish-born sculptor José de Arce sparked a shift in

Andalusian sculpture away from the naturalism of

Montañés and his followers towards a greater concentration

on atmosphere and movement.

3 C. LÓPEZ MARTÍNEZ, Desde Martínez Montañés hasta

Pedro Roldán, Seville 1932, p. 231.

4 Commissioned by the Guild of Glovemakers for the parish

church of El Salvador, this work, which is over two metres

tall, was painted and decorated to the highest standard and

debuted as part of a processional in 1598.

5 C. RODRÍGUEZ MORALES and P. F. AMADOR MARRERO,

Comercio, Obras y Autores de la Escultura sevillana en

Canarias (siglos XVI y XVII), in El Señor a la Columna y

su Esclavitud, La Orotava 2009, p. 183.

6 SOTHEBYS, A Spanish Painted Wooden Figure of the

Christ Child, from the Workshop of Juan Martínez

Montañés, in Old Master Paintings and Sculpture, New

York 2009, lot. 347.

7 See H. VAN OS ET AL., The Art of Devotion in the Late

Middle Ages in Europe, 13001500, exhibition catalogue,

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam 1994, pp. 100103.

8 J. LUIS ROMERO TORRES and A. TORREJÓN DÍAZ, Niño

Jesús, 1607, Francisco de Ocampo, atribución, in San

Isidoro del Campo (13012002), Fortaleza de la

espiritualidad y santuario del poder, Seville 2002, pp.

176179.

Private Collection, New York