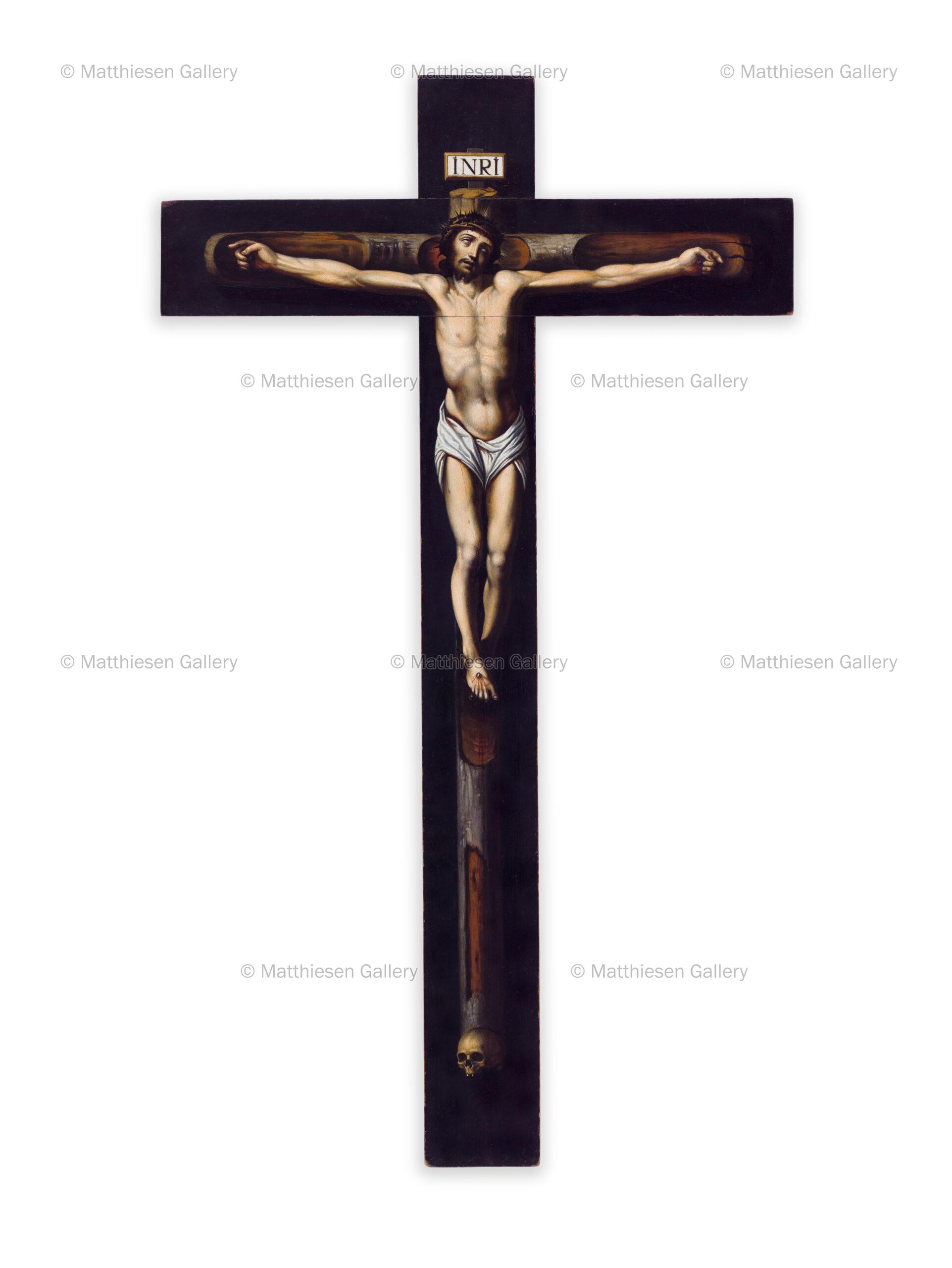

Crucifix(María Josefa Sánchez)

THE CELL CROSS IN EARLY MODERN SPAIN

Cell crosses (cruces de celda) are small painted or sculpted crucifixes commonly used in private devotional practice in monasteries, convents, and private oratories. As vehicles for prayer, self-examination and meditation on Christ’s sacrifice these objects facilitate a focus on personal reflection that was popularised in Ignacio Loyola’s Exercitia Spritualia (Spiritual Exercises, 1548), Fray Luís de Granada’s Libro de la oración y meditación (The Book of Prayer and Meditation, 1554, revised 1566) and Teresa de Jesús’s Camino de Perfección (The Way of Perfection, 1566). The use of the cell cross as an object of devotion can be seen in many early modern paintings of saints and holy women and men, including El Greco’s St Francis in Prayer before the Crucifix (1585, Bilbao Fine Arts Museum), Luis Tristán’s St Jerome (early 17th century, Madrid, Prado Museum), Diego Velázquez’s Madre Gerónima de la Fuente, (1620, Madrid, Prado Museum), Bartolomé Esteban Murillo’s Sor Francisca Dorotea embracing a crucifix, (1674, Seville, Cathedral, Capilla de Santiago), and anonymous portraits of nuns that are ubiquitous in Spanish convents. In 1658 the painter Juan Carreño de Miranda presented a cell cross to King Felipe IV inscribed with a dedication in Latin (Indianapolis Museum of Art). Similar crosses painted by Murillo around 1670 have been identified.[1]

MARIA JOSEFA SANCHEZ AND CLEMENTE SANCHEZ

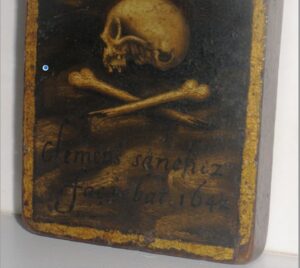

Working within this cultural framework, María Josefa Sánchez produced at least fifteen painted crucifixes, probably in Castile, between 1639 and 1652. It has been argued that Sanchez might have been a nun or a novice since the use of the word Doña in her signed crosses might suggest that she could have been a noble woman, and the existence of signed works indicates a certain level of recognition and prestige. In several versions the artist’s signature appears between a tuft of grass at the base of the cross: D.MR Josepha Sánchez /faciebat, followed by a date. Two crosses using the same model have been identified bearing the signature of Clemente Sánchez, a minor painter who practiced in the Castilian town of Aranda del Duero in the mid seventeenth century.[2] Clemente’s crosses both bear the inscription CLEMENS SANCHEZ at the base, and are dated 1642 and 1646, years when María Josefa was also producing works that bore her name (see Fig. 2).[3] The two painters are likely to have been related.

|

|

|

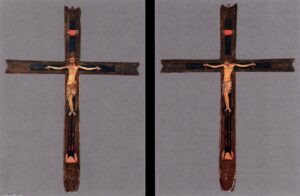

| Fig. 1 Cell Cross, 1646, oil on cruciform panel.

63 × 39 cm Signed at base Maria Josefa Sanchez Chicago Art Institute https://www.artic.edu/artworks/242449/crucifixion Detail of signature below |

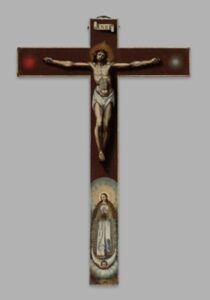

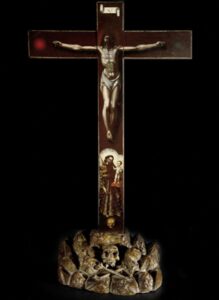

Fig. 2 Crucified Christ, 1642, oil on cruciform panel.

59 x 34 cm Signed at base Clemente Sánchez Palau Antiguitats, Barcelona. Detail of signature below |

|

|

THE SMALLER SANCHEZ CELL CROSSES

Most of the modest objects by Maria Josefa and Clemente Sánchez comprise two narrow wooden panels of approximately 10cm width, spanning around 50-60cm in length and 30-40cm width from the edges of the arms.[4] Most were constructed with the lateral piece lapped beneath the vertical. The support was prepared with a dark paint, and the edges of the cross were outlined with a thin line painted either in a light colour or gilt, some of which has worn away over the years by the hands that grasped the object. A cartoon or template was then applied, from which an image of the crucified Christ and a cartellino was traced onto to the wooden support. The emaciated, elongated figure follows the vertical and horizontal lines of the crucifix. Secondary figures at the lateral edges and the base may include the sun and moon, the Virgin Mary, St Anthony, a young girl or a skull. When a signature is present it is at the base of the cross, usually among grasses. Cell crosses were often produced anonymously and are only rarely associated with specific artists. The striking repetition of form and execution in María Josefa’s small, devotional images indicates the existence of a popular, probably localised, demand. The variation in the secondary details painted on each cross suggests that they were produced as individualised commissions.

THE MATTHIESEN CELL CROSS

The principal purpose of this object was to be a vehicle destined for devotion and introspection. Deeply rooted in Spain’s mystic tradition, this representation of the crucified Christ conforms to Tridentine exhortations that visual excess should be stripped away to foster a heightened sense of spiritual connection. Appropriately for a devotional object that was most likely not designed for public display, Maria Josefa Sánchez’s cross is devoid of artistic flourishes. The viewer is invited to confront the powerful subject matter without the distraction of secondary details, besides the presence of a skull at the foot of the cross beneath Christ’s feet.

Fig. 3 Giunta Pisano (also known as Giunta Capitini), Processional Cross, Venice, Cini Foundation.

The work under review measures 91cm x 52cm, around 30cm longer and 15cm wider than the other crosses we currently know. The crucified figure is painted in a mannerist style, that reflects the artist´s knowledge of, and interest in, other representations of the theme that were disseminated throughout Spain through prints, notably those of Luis Tristán. María Josefa’s depiction of a cross made of an unfinished tree trunk rather than prepared, smoothly planed wood may relate to a similar feature seen in Luis Tristán’s Crucifixion of c. 1613, Museo del Prado. However, an Italian painter, Angelo Nardi (1584-1665), also working in Spain, used a very similar naturally hewn tree trunk in his crucifixion, now in the Bowes Museum. The motif of a cross within a cross may be seen as early as the processional Crucifix by Giunta Pisano, c.1250, in the Cini Foundation Collection, Isola di San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice (Fig. 3), and also in the Crucifix by Paolo Veneziano, c.1350, in the church of San Giacomo Dall’ Orio in Venice. It is not a common representation but in Spain it was taken up in the XVII century by Murillo. The fashion for naturally hewn tree trunks can also be seen in French art of the first half of the XVII century and was also adopted in Germany in the late Medieval period.

In her catalogue entry for the cell cross by Sanchez that was recently acquired by the Meadows Museum, Amanda Dotseth draws stylistic comparisons between Sanchez and a much earlier, mannerist painter, Luis de Morales, whose work was widely disseminated through prints, but in reality, the present cell cross owes more to the realism of Zurbaran, a slightly earlier artist than Sanchez, rather than to the mannerism of Morales.

Light from the left illuminates Christ’s elongated human form, defining the musculature of the stomach and the lower ribs, the clavicle, and the gaunt arms that emphasise the elbow joint. Shadow is also used to indicate the slight twist to the hips, caused by the single nail that secures both feet onto the cross. The same shadow obscures the lower left leg and foot. The emaciated physical human form highlighted by a raking light recalls the more mannered Luis de Morales’ Crucifixion of 1566 in the Museo del Prado. Christ’s body appears almost weightless, as if he is floating rather than nailed onto a cross. Dark shadows painted around Christ’s figure produce a silhouette-like, tenebrist effect. This gives an uncanny sense of his detachment from the cross to which both his hands and feet are nailed, thus conveying the impression that the body is somehow independent of the wooden support. A sense of physical separation from the cross extends to the head, which projects forward towards the viewer’s right. The shadowed outlines may have been inspired by a knowledge of Francisco de Zurbarán’ s painted scenes of the crucifixion emerging from darkness, which appear almost sculptural, such as in the latter artist’s Crucifixion, c. 1635, Museo de Bellas Artes, Seville. Whereas in some cell crosses, such as that in Chicago (Fig.1), Christ is represented as Christus Triumphans, in our picture Christ appears in his final moments, expiring. Both the Matthiesen, Meadows and Chicago paintings lack the spear wound in Christ’s side which the gospel (John 19:34) relates resulted from the Roman soldier, Longinus’ spear. This event took place after Christ had died on the cross and its submission underlines the fact that the worshipper was intended to still contemplate a living Christ who is still actively undergoing his torment by crucifixion. This torment is accentuated as Christ looks upwards and to his left, the anguish communicated by his rolled up, half-open eyes in anticipation of his approaching death. His closed mouth reminds the viewer that his physical suffering on earth served a higher purpose, in the service of which he accepted his self-sacrifice in expiation of human sin. The unsparing depiction of the figure in the final moments of His suffering accords closely with contemporary devotional imagery.

The depiction of a partially carved tree trunk as the instrument of Christ´s death (see above) is a significant differentiator between this and other known works. The worshippers who held the smaller crosses depicting the human form nailed directly onto the support were ostensibly more directly in contact with the instrument of Christ’s death. The insertion of the tree trunk (a cross within a cross) between the support and the painted figure of Christ changes this relationship between the viewer and the object. At over 90cm in length this cross may have been primarily intended for display on a cell wall and not so much as a cult object to be handled as much as the smaller crosses were effectively utilised.

The Matthiesen work appears to be a more accomplished painting than the smaller crosses signed by María Josefa and Clemente Sánchez, most of which shared a common cartoon, and depicted elements (for example the loincloth) with identical strokes of a paintbrush. The structure, design, and details in this larger work are very similar but because of the size, it is unique, at least until another cross of this type and size becomes known.

With only two signed works by Clemente a persuasive comparison of the two artists is impossible. Based on current understanding and an assessment of quality this work, held by Matthiesen is more likely painted by María Josefa Sánchez.

Many modest cell crosses remain on convent walls, echoes of another time. The recent, gradual increase in interest in these objects and the discovery of María Josefa’s signature on some, may lead to more research and discoveries about the identity and the working context of this painter, adding to the steadily growing list of women artists who lived and worked in early modern Spain[5].

[1] Carreño´s Crucifix is discussed in Rhonda Kasl, (ed) Sacred Spain: Art and Belief in the Spanish World, Exhibition Catalogue, Indianapolis: Yale University Press, 2009, p. 300, no. 60. Valdivieso identified three small crucifixes by Murillo in Murillo: Catálogo Razonado p. 184 and p. 445, nos. 260, 261, 262.

[2] Fernando Collar de Cáceres, ‘Sobre algunas cruces pintadas’ (1989) and ‘Varia inmaculadista (algunas pinturas seiscentistas inéditas o poco conocidas).’ Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y Arqueología: BSAA. 64, (1998): 369-393 especially pp. 377-378. René J Payo Hernanz mentioned paintings by Clemente Sánchez in ‘Notas para el estudio de la pintura de la ribera burgalesa del Duero durante los siglos XVII y XVIII’, Biblioteca: estudio e investigación, 19, (2004): 265-318.

[3] A cross bearing Clement Sánchez´s signature (Fig.2) was advertised in late 2022 by the antiquarian Palau Antiguetats in Barcelona, and another was auctioned in December, 2022 by Templum Auction House, also in Barcelona. A third, unsigned version was advertised by the antiquarian Noel Ribes in Valencia. The three designs repeat that of Marìa Josefa´s cross in Oberlin College, with the sun and the moon at the arms with the addition of St Anthony of Padua and the Christ Child at the base. Two (one signed, one attributed), sit in a carved, polychromed wooden representation of Golgotha.

[4] We are grateful to Cathy Hall-van den Elsen for this text entry which was edited with additions by the Gallery.

[5] María Josefa’s crucifixes have been identified in convents in Segovia, Carrión de los Condes, Zamora, auction houses in Barcelona, Buenos Aires, Madrid and Valencia and museums in Chicago, Dallas and Oberlin, Ohio.

Private Collection, Barcelona.

C.G. Perez-Neu, Universal Gallery of Women Painters, 1964;

J. De Mesa and T. Gisbert, ‘Una Pintora Española del Siglo XVII: Josefa Sánchez’, Archivo Español de Arte, Madrid, volume 43, n.169, pp. 93-95, 1970;

M.A.F Mata, ‘Un crucifijo de la pintora Josefa Sánchez: Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas’, Reales sitios 17:66, 1980, pp. 65-67;

F. Coral de Cáceres, ‘Sobre algunas cruces pintadas de María Josefa Sánchez,’ Estudios segovianos, XXX, 30:86, 1989, pp. 355-373;

F. Coral de Cacares, ‘Varia inmaculadista (algunas pinturas seicentistas ineditas o poco conocidas)’, Bollettin del seminario de estudios de arte y archeologia: bsaa,64, 1998, pp. 369 – 393 and particularly pp.377-378;

A. Rivera de las Heras. ‘Cruz de celda’ in El Arbol de la Cruz: Las Cofradías de la Vera Cruz Exh. Cat., Museo Etnográfico de Castilla y León, 2009: p. 107;

Spain: Art and Empire in the Golden Age, Exh. Cat., San Diego Museum of Art, 2019;

Maria Josefa Sanchez Crucifixion, Art Institute of Chicago, 2019, https://www.artic.edu/articles/780/maria-josefa-sanchezs-crucifixion;

C. Hall-Van den Elsen, Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400 to 1800, Baltimore Museum of Art and Art Gallery of Ontario, 2024;

J. Hernandez Miranda, El Meadows Museum Anuncia la Adquisición de dos pinturas de mujeres artistas del Barocco, published by the Meadows Museum, 2024;

C. Hall-Van den Elsen, Gender and The Woman Artist in Early Modern Iberia, Routledge, London 2024, pages 37-40.