Salvator Rosa

Place Born

NaplesPlace Died

FlorenceBio

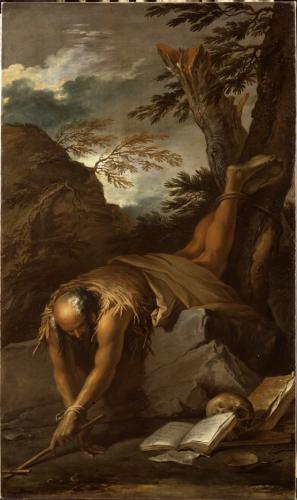

Salvator Rosa’s reputation as a picturesque Gothick painter of brigands and landscapes dates mainly from the eighteenth century. It was encapsulated in Lady Morgan’s two volume Life and Times of Salvator Rosa, published in 1824. Recent research and reappraisal, however, has revealed Rosa as a many-faceted talent, who drew not only on the resources of the visual arts but also on literature and music. Although Neapolitan by birth, he absorbed many unexpected features from his two adopted cities of Rome and Florence. It was perhaps mainly to the latter’s ambiguous mixture of tortured religiosity, repressed sexuality, bizarre sub-cultures and irrepressible sense of ironic humour that Rosa was most attracted.

A welcome eclecticism characterises Rosa’s artistic sources. Although he studied with Aniello Falcone, he also found sympathetic elements in painters as diverse as Poussin, Ribera, Castiglione, and the Florentine Cecco Bravo. Through his brother-in-law, Francesco Francazano, he no doubt personally knew Ribera. Rosa’s main output was of landscapes, which tend towards the sublime in their precipices, jagged trees, and dramatic, theatrical distances that often recall the coastal scenery of Naples.

Rosa’s early Neapolitan pictures were small bambocciate-like genre scenes, which became more ambitious after he moved to Rome in 1635. Between 1640 and 1649 he worked in Florence, where he created a number of celebrated seascapes and battle scenes.

Under the influence of Florentine painter-poets, such as the amateur philosopher Lorenzo Lippi, Rosa painted not only deeply introspective images imbued with philosophical intent but also scenes of black magic and inexplicably disturbing (and not wholly successful) religious pictures. Works such as his Humana Fragilitas (Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum) provide a link between seventeenth-century moralising and obsession with time and the later romantic emphasis on emotive visual effects.

After 1660 Rosa began to produce etchings, which spread his love for the Picturesque above all to Britain. His strongly independent nature and obsession with artistic individualism helped to formulate an image of him as an isolated genius struggling to achieve a unique vision.