Blasco de Grañén

Place Born

ZaragozaPlace Died

ZaragozaBio

Christ on the Cross is by far the most frequently encountered theme in 15th -century Spanish imagery, whether painted, carved and polychrome in wood or cast in metal. A crucifix was an obligatory piece of church furniture on any altar during the celebration of mass. Crucifixes were carried in religious processions and painted or sculpted examples were to be found at the very top of every multi-paneled retablo or altarpiece, especially in the region of the Kingdom of Aragon (Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Islands).

Many of the polychrome sculpted works for altarpieces carried a streamlined iconography: Christ on the cross with the mourning figures of the Virgin Mary and St. John the Evangelist to either side. Other paintings told the complete narrative, replete with sanctified mourners, Roman soldiers including the repentant Longinus and sometimes the two other crucified thieves as well.

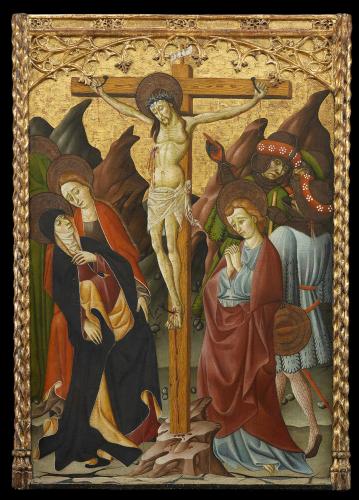

The painted example by Blasco de Grañén shown here falls in-between (Fig. 13). A rather small Jesus is fastened with bent nails to the cross occupying centre stage; the Virgin Mary, fainting, is sustained by a saintly female and another cloaked, haloed figure with his back turned and to the right. To his left (the sinister side) are three Roman soldiers, dressed as contemporary mercenaries. The soldier pointing to the cross is probably Longinus, who recognized Jesus as the Son of God. In front of these men stands the young St. John the Evangelist, hands clasped in mourning, wearing biblical robes. All these figures occupy a desolate landscape – more like a stage-set than anything else. Behind everything is a gilded sky.

This painted panel is not an isolated icon but an expected and integrated part of the larger scheme of the retablo and it occupied a set position. Spanish retablos ranged from the mid-sized for small chapels, up to the colossal in scale for high altars. These were called retablos mayores and often completely filled the main apse of a church. They generally consisted of a wide central calle, or vertical zone, with its largest image, a formal one of the saint to whom the altarpiece was dedicated, forming the liturgical centre. Placed over the principal effigy was the Crucifixion, smaller than, but often as wide as, the main image.

Surrounding it would have been tiers of narrative scenes giving details of the life of the central saint. This constituted the body of the retablo. It in turn rested on a banco, a horizontal strip as wide as the body, also painted with smaller scenes generally depicting either episodes from Christ’s Passion (whatever the main topic of the retablo) or images of other saints, usually determined by the patron. If the altarpiece were for a chapel, the centre of the banco, lining up with the main image and Crucifixion, would contain the dead Christ in his tomb; if the work were for the high altar, this position would be occupied by a gilded wooden tabernacle, a repository for the consecrated reserve host wafers. Lavish gilded frames were placed around each painted panel, usually arched in the lower tiers, and with pointed frames called chambranas crowning the upper tiers. In elaborate retablos there might also be tubas or linternas, projecting canopies of tracery. The entire body would be surrounded with framing guardapolvos or dustguards, tilted slightly inwards, generally adorned with the coats of arms of the people who had paid for the altarpiece, and sometimes also smaller images of saints. To understand the individual elements you had to see the whole colourful ensemble: central images for contemplation and a reminder of the eucharistic nature of the mass, side narratives for education, particularly when many parishioners could not read or write.

When faced with an isolated Crucifixion from this time and place, if its location of origin is not known and documentation concerning it does not exist, it can be extremely difficult to identify its original context unless it was located at the top of an altarpiece. The identity of the master and workshop that produced the present piece is known and it was certainly part of a much larger construction, probably done by the most prestigious retablo firm in the Aragonese city of Zaragoza during the second third of the 15th century.

The master painter was Blasco de Grañén, who worked in Zaragoza from 1422 until his death in 1459. Much documentation about Blasco survives. Contracts or payments still exist for at least 24 altarpieces, many vast in scale, plus painted coffins, painted curtains and painted draperies for funerals. In addition, there are many undocumented works, identifiable by style, attributed both by María Carmen Lacarra Ducay and, earlier, under the name of the ‘Master of Lanaja’, by Chandler R. Post who died 25 years before the painter’s true identity was known.

Documents have revealed that over his career Blasco employed a number of apprentices, many from other regional families of painters (including Miguel Vallés, Jaime Arnaldín, and Miguel de Balmaseda), and he probably trained his nephew Martín de Soria who succeeded him. In addition, he collaborated with other master painters, a frequent practice in late-mediæval Aragon, including Jaime Romeu. He was also a witness to legal transactions relating to other masters, including Pascual Ortoneda and Pere García de Benabarre. All of this is evidence of the close professional and dynastic relations in the art world in Aragon at this time, although he sent his own son, Bernardo, to Barcelona to be apprenticed to the even more sophisticated painter, Bernat Martorell.

Since several commissions were normally worked on at the same time, Blasco must have been running a virtual factory, employing assistants as well as apprentices and gilders, and either kept a carpenter on hand or subcontracted. Individual panels were often quite large and heavy, constructed with well-seasoned boards glued together and supported by bars on the back smoothed down to uniformity. The preparation and painting took considerable energy and physical strength. Coats of gesso, both rough and smooth, and gilding were generally applied before painting. The medium itself was normally tempera, the colours ground in the shop and mixed with an egg-yolk binder (or other binders such as glue for certain hues). Just coming into fashion in Blasco’s time was the incorporation, in many of the biggest formal images, of embutido which means ‘stuffed’ : modelled and stamped borders and adornments of raised and gilded gesso making the brightly painted surfaces even richer. The frames were made by the carpenters and then gilded. Architectural in nature they replicated the stone tracery designs in the architecture surrounding the retablo and, in documents, even shared the same terminology for specific decorative parts. Grañén and his workshop produced extremely large retablos, not only for churches in the city of Zaragoza, but also for parish churches and convents all over Aragonese territory, particularly in what today constitutes the provinces of Zaragoza, Huesca and probably neighboring Teruel as well.

Transport and installation, particularly to distant or remote locations, also offered challenges. The individual panels and framing elements, covered in sheets, would be loaded onto a mule train and a shop employee or a crew of them would travel to the site to fasten each weighty panel into place and then nail on the framing elements.

These constructions were made to be durable, the colours very bright and the gilded details highly burnished in order to be seen illuminated by whatever windows, candles and oil lamps their sanctuaries possessed. Though so many retablos have been divided, damaged and destroyed over the centuries, many have survived as an ensemble remarkably well.

An impressive example by Blasco and his workshop, which, though undocumented, contains all the elements and the painting style of his production, survives in the small town of Anento (Fig. 14). The reason for its virtually intact state probably lies in the fact that until late in the 20 century the town was accessible only by footpath along a rocky riverbed.

Since the apse of its church, dedicated to St. Blaise, is flat, the retablo mayor was made to occupy the entire space and is stepped at the top to accommodate to the vaulting. There is unusual variety here in the size of individual images and narratives within their calles to accommodate the spatial variations of the apse and its large dimensions. The altarpiece bears a triple dedication to the Virgin of Mercy, St. Blaise and Thomas à Becket with three large images, each surrounded and surmounted by narratives. It is one of the few high altarpieces that still retains its gothic carved and gilded tabernacle in the centre of its banco, which is flanked on either side by five scenes of Christ’s passion. The coats of arms of two archbishops of Zaragoza are incorporated, Francisco Clemente Çapera (1415 – 1419 and again in 1429) and Dalmau de Mur i Cervelló (1431-1456). Scholars assume that most of the work was done during Dalmau de Mur’s tenure. Given the limited size and remoteness of Anento, the endowment of such a large work must have been due to its donors. Dalmau de Mur was a prodigious art patron ordering and financing works for both cities and countryside during his long career. The Anento retable was not the only work he would order from Blasco de Grañén’s workshop. The painting seems to have been executed by several people, with consequent variations in quality and ability in the individual panels, although the overall effect is dazzling and recent cleaning has revealed its overall high quality of workmanship.

Due to the altarpiece’s vast size, most worshippers would not have been able to see the upper panels in detail and Lacarra remarks that the second horizontal tier in the retablo’s body shows less quality than the banco and the larger images and narratives on the first tier. This was not unusual in these large altarpieces where the best workmanship and colours were often reserved for those portions closest to the viewer. The largest images of the retablo’s dedicated saints are brilliant examples of the great formal sweep typical of such effigies throughout the career of the Blasco de Grañén workshop. The surface-oriented juxtaposition of multiple patterns provides reinforcement to the virtual carpet of painting that characterises the whole production.

However 21st . century taste may judge the painting of the high altarpiece of Anento, Blasco Grañén’s contemporaries thought he was just fine – indeed better than merely fine. He was able to ask very high prices for his large works, up to a colossal 10,000 sueldos for the retablo mayor for the church of San Salvador in Egea th de los Caballeros for which he was commissioned in 1438 – a sum so large for the time that the parishioners who were financing it had trouble in meeting payment deadlines and the work wasn’t completed until 1476, long after Grañén’s death, by his successor, Martín de Soria.

Many of the altarpieces both he and his studio worked on were dedicated to the Virgin Mary, not surprising in the case of high altar retablos since many churches were consecrated to her at this time. Given the vast dimensions of many of these works, it is not surprising to find the same narrative scenes repeated over and over with the emphasis on clarity of story-telling. The workshop must have had a collection of basic compositions with set characters for each tale, though they took pains to make special variations in each perhaps to keep themselves from getting bored with the seemingly endless repetitions. This is probably even more true of the crowning panels of the Crucifixion in each altarpiece, no matter which saint held the main dedication.

For the large central effigies of the Virgin Mary, Grañén developed a prototype that proved very popular. Since the individual patron or group of patrons had the final choice in the approval of the finished product, it proved a successful template.

This was particularly evident between 1437 and 1439. Perhaps the best example is a panel now in the Museo de Bellas Artes in Zaragoza, which constituted the centre of an altarpiece commissioned by city officials and citizens of the town of Albalate del Arzobispo in 1437 and completed two years later (Fig.15). The archbishop was once again Dalmau de Mur, whose coat of arms appears in the surviving central panel. This work too was relatively costly for the time at 6000 sueldos. The details of the contract have not survived and presumably the narrative and banco panels are long gone but the central panel was moved from the parish church to that of San José in the same city sometime before 1914.

The remarkable thing about this panel of the Virgin and Child with eleven angels, eight of them playing contemporary musical instruments, is that it still makes an impressive stand-alone composition and serves as the ensemble’s focal point. The Virgin, dressed in traditional colours, a red dress and blue brocade mantle which is now darkened almost to black with a white ermine lining, sits on an elaborate throne. Her cloak has a border of gilded embutido with green accents and her crown and halo and the Christ Child’s halo are also of richly patterned embutido, while the angels have flat gilded haloes. There is more gold in the brocade background and embutido highlights pick out the coat of arms of Dalmau de Mur, held by another angel. The Christ Child wears a purple robe and a sprig of coral around his neck. He blesses with one hand and holds an orb in the other. There is an apocalyptic reference in the twelve gold stars that surround his mother’s halo.

All of these elements are standard Virgin and Child iconography of the period. What makes the image so impressive is its symmetry with the throne framing the Virgin and Child, like an even larger more splendid halo, the broad surfaces of painting and patterning in the grounds, brocades and the positioning of the figures themselves. The embutido tends to emphasize surface over depth; to modern eyes it is almost an abstraction of patterns but it is the perfect foil to bring the eye back to the surface of the ensemble. In a large retablo a strong emphasis on depth in so many diverse panels, be they formal effigies as here or more complex narratives, would be lethal in the context of the whole – rather like a window of many panes with a different scene and view in each. Here, the effect is of a magnificent screen and Grañén and his shop had developed the perfect synergy between formal image and narrative. It is ideal for the retablo format.

The template for the Virgin and Child image of Albalate proved so popular that the workshop used it on at least three other occasions in differing situations within a two-year period. Once it was employed in a retablo for a private patron in a monastery chapel in the Convent of San Francisco in the city of Tarazona. The chapel, the last on the left of the nave, was dedicated to Our Lady of the Angels.

Its patron bore the unlikely name of Esperandeu de Santa Fe, which translates roughly as ‘Waiting for God of the Holy Faith’. Esperandeu was not born with this name: he was originally Ezequiel or Ezmel Azanel and came from a wealthy Jewish family, one of the most prominent merchant clans of Tarazona. He converted in 1413/14, convinced by Christian arguments at the disputations taking place in Tortosa between Christians and Jews. For the new convert there was an enticement as well: he was made a knight, given the exalted prefix Mosén to use before his name, and allowed to wear the spurs of nobility. He is depicted thus in the central panel of his retablo (Fig. 16), kneeling at the foot of Christ and the Virgin with an angel at lower left holding his recently designed coat of arms (a hand holding a cross of Lorraine). The inscription in the centre reads The very honorable Mosén Sperandeu de Sancta Fe had this retablo made in honour of the glorious Virgin Mary, and it was completed in the year fourteen thirty-nine. It is a public statement of his Christianity. This panel is now in the Museo Lázaro Galdeano in Madrid. The Virgin and Christ Child are in almost identical poses to the ones from Albalate but in even brighter colours, once more with lavish accents in embutido. Here there are only six angels, four playing instruments, probably because the donor and his inscriptions and emblems take up so much space. Perhaps appropriately for a patron who was also a convert, there are no gold stars around the Virgin’s halo. Perhaps he did not yet want to consider the concept of the Apocalypse.

The original retablo was again quite large. The contract calls for 15 panels, nine narratives of the life of the Virgin (presumably the central panel was one of these), plus five in the banco of Christ’s passion. Though the Crucifixion isn’t mentioned, it probably constituted the fifteenth panel since the other scenes would have had to be of an even number for symmetry. It was commissioned in 1438 and completed the year after.

There is no information on when the Albalate retablo was taken down and divided but it is possible to make an assumption about Esperandeu de Santa Fe’s. In 1835, Isabel II’s Liberal prime minister, Juan Álvaro Mendizábal published a proclamation of desamortización, the secularizing and selling off monasteries and convents with less than twelve members in order to raise money for the wars against the Carlist pretenders to the throne. Although this was ostensibly justified by dividing some of Spain’s considerable monastic properties between small farmers, the eventual beneficiaries were generally wealthy. The edict led not only to the dissolution of many monasteries that had flourished for centuries, but also to outright plunder. It was then that many monastic retablos were confiscated, cut up and sold. Like the monasteries’ properties themselves, many went into the private holdings and collections of the aristocracy and, in industrial cities like Barcelona, the growing bourgeoisie.

After the desamortización, the convent complex of San Francisco remained uninhabited and many of its dependencies passed to the municipal government. The church itself remained in use, maintained by the Third Order of Saint Francis; at the beginning of the 20th century it became a parish church. The complete history of Esperandeu’s altarpiece is unknown but the central panel was in the collection of Cesário de Aragón, Marqués de Casas Torres, in Madrid until around 1910 when he sold it to the Lázaro Collection, later the Museo Lázaro Galdeano. In 1952, fragments of some of the narratives were found in the detritus of a pile of wood used for roof repairs stored under the eaves. Now in the Casa Consistorial in Tarazona, they represent fragments of three scenes from the banco (The Kiss of Judas, The Washing of Feet and The Flagellation) and two from the Life of the Virgin (The Circumcision and Christ among the Doctors).

Could our Crucifixion have been a part of this retablo as well? The measurement of the central panel of Esperandeu’s altarpiece is 167 x 107 cm., the Crucifixion measures 145 x 100 cm. Normally, the Crucifixion, occupying as it does part of the central vertical section of the retablo, would be as wide as the main image but sometimes there are discrepancies, particularly if there is an intervening panel with the Coronation of the Virgin that could taper at the top (as was the case for the Retablo of the Virgin from Tosos, discussed below).